Transcript of a press teleconference on Zimbabwe's humanitarian crisis, which continues to rapidly deteriorate, causing appalling suffering. MSF's medical teams have now treated almost 45,000 people for cholera, and the crisis is far from over.

Dr. Christophe Fournier, MSF International Council President; Manuel Lopez, MSF Head of Mission for Zimbabwe; and Rachel Cohen, MSF Head of Mission for South Africa spoke on a press teleconference from Johannesburg. Dr. Fournier just returned from assessing MSF’s medical programs in Zimbabwe this past weekend. The following are excerpts from the briefing.

Dr. Christophe Fournier, MSF International Council President

Listen:

Good morning everybody, and thank you for being with us today.

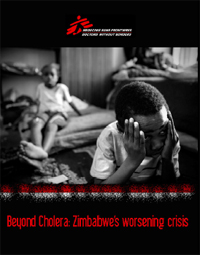

I have just returned from visiting our teams in Zimbabwe to assess our medical programs. What I witnessed in the last few days is the kind of health crisis that we as MSF doctors usually only see in war zones, or in countries in the immediate aftermath of conflict. Zimbabwe is a country literally falling apart at the seams.

Cholera is the most striking, and certainly the most visible, symptom of this incredible health crisis. MSF has mobilized massively to provide medical and logistical support in Zimbabwe, supporting the treatment of 45,000 cases – approximately 75 percent of the burden nationwide. In the first week of February, 4,000 new cases were treated in MSF-supported hospitals and clinics. The epidemic is far from over. We need an emergency response equal to the disaster unfolding before our eyes.

But beyond the cholera epidemic is a total health system collapse. Cholera is the tip of the iceberg.

Health facilities are closed and patients simply cannot access health care. Medical staff has fled because they are not paid; there is an acute shortage of essential medicines and medical materials; and in those few places where services are still available, patients cannot afford care as they have to pay in foreign exchange.

The World Food Program has said that 7 million people are in need of food aid – far more than half of the population. In the MSF program in Epworth, the number of malnourished children has quadrupled since November . We have seen people so desperate for food they are actually disappointed when they find out they are not HIV-positive because they are not eligible for food aid.

One in five adults in Zimbabwe is infected with HIV, and too few of those in urgent clinical need of treatment can access antiretroviral therapy (ART). MSF is supporting HIV care for 40,000 people with HIV, 26,000 of whom have been initiated on ART. But our patients are increasingly missing their appointments because they can't get to clinics due to transport costs or because they have had to flee to neighboring countries, especially South Africa. We are extremely concerned that this could result in treatment interruptions and, eventually, drug resistance.

Despite these glaring needs, the government of Zimbabwe has failed to allow humanitarian organizations to provide assistance in the necessary timeframe, exerting rigid control over many aid agencies and politicizing the delivery of humanitarian relief. Even in the face of 2,000 cholera cases per week in the capital, it took our medical teams weeks to get permission to open another ward in Harare’s Infectious Disease Hospital.

And donors and UN agencies have not yet shifted their mindset toward an emergency approach or de-linked the provision of humanitarian aid from the political process. Before summarizing what precisely MSF is calling for today, I would like to ask my two colleagues to give brief remarks about MSF's medical programs in Zimbabwe and our projects for Zimbabweans seeking refuge in South Africa.

First, I will turn the discussion over to my colleague Manuel Lopez, our head of mission in Zimbabwe for the past two years.

Manuel Lopez, MSF Head of Mission for Zimbabwe

Listen:

Thank you, Christophe. Good morning, everybody. Having been in Zimbabwe for two years, I have witnessed that the situation has been worsening. I definitely would like to speak about cholera, but I would like to concentrate on a general assessment of the crisis because it’s really a medical emergency that’s spiraling out of control. So I think that we really have to focus on the problem of access to health care, but of course I have to say that the cholera epidemic that started in August is far from being over. In the last week of January and the first week of February, we’ve had the highest number of cases since the epidemic started in August, still affecting all the ten provinces in Zimbabwe and 56 out of 62 districts in the whole country so we are far from over. MSF is struggling to cope with all the needs and it has contributed and supported the consultations and treatments of 45,000 suspected cholera patients. This is the magnitude of the problem. We don’t know what’s going to happen in the future, but we feel that there are many possible scenarios. One is that cholera is going to continue to cause hundreds of deaths before the epidemic is over because the water and sanitation system is in such a situation. We still see some water systems being contaminated and causing explosions of cases in some of the cities in Zimbabwe, like we have seen in Beitbridge, Chegutu and Kadoma, and in other places in the past weeks. But yes, I have to insist that those who have died and those that we’ve treated, have been treated or have died in the last two to two and-a-half months. So yes, I would say that it is still a situation that requires a huge struggle, a huge effort to be dealt with.

But as I said, this is only one part of the problem. I would like to say also something about how people endure the situation in Zimbabwe. When patients go to the clinics, they find many times that the clinics, health facilities, hospitals, and the district hospitals are closed. Or if they are open, there are no doctors, there is no medicine available, there are no resources. X-ray machines don’t work. There is no possibility of a proper diagnosis. And many times, if a patient needs to have a consultation and treatment, they must pay between two and three U.S. dollars, which for most of the people living in the rural areas or in the suburbs is almost impossible. They simply cannot afford to do that. So many of them stay at home or die at home. So that’s the way it is. It gets as hard as that.

The maternity wards are also closing in Zimbabwe. Less and less pregnant women are going to the clinics to deliver because they have to pay this huge amount of money, and prenatal care already costs more that 20 US dollars. And most of the people, as I said, cannot afford this amount that they have to pay in foreign currency. Also, when they go to deliver, sometimes they have to bring their own water, or they have to go to the pharmacy to buy the gloves for the midwife or the nurse because these items are not available in the clinics anymore.

We also see that dead bodies, the cadavers, are piling sometimes in the hospitals because the families don’t have the money to afford funerals. Therefore the health care workers, they don’t know what to do with the dead bodies in the hospitals. They don’t even have proper disinfection resources or body bags. And MSF has to deal with these problems in the hospitals of the areas in which we are working. Of course, I can only say that I don’t see the situation improving. As I said at the beginning, the situation is out of control and it’s a medical emergency. And we don’t know how it is going to progress in the next months.

Just for you to understand what I was saying earlier about the closing of the clinics: Since the cholera epidemic started, we’ve seen many district hospitals in Zimbabwe that have closed because they didn’t have enough human resources support to cope with adding a cholera treatment center to all the other running facilities. Clinics are closing because the hospital staff is not getting paid, or they are getting paid the equivalent of $1.80 U.S. dollars per month. This has caused strikes all over the place. Sometimes you don’t know if the staff is striking or if they just don’t have the money to pay for transportation to work, because with this salary they cannot pay $1 per trip for a public bus in Bulawayo. So for example, in Bulawayo, 19 clinics have been closed for three weeks because of the strikes. Now they are slowly opening because some nurses have started to go back to work with the promise that they will get their salaries. Of course many of them are still waiting for the salaries and we don’t know what’s going to happen. The situation is repeated all over the country and we are afraid that many clinics will continue to close in the future.

Of course this means that people want access to treatment, want access to consultations. When you see that the situation in the country, the health care situation, is combined with restrictions for our doctors to provide medical care, then you understand that something is very wrong. Our doctors, our nurses, and everybody that we bring to help with the crisis from abroad, they have to wait between three and six months to get a working permit. When they finally get a working permit, doctors have to do additional training of three months in Zimbabwe before they are allowed to perform any clinical work. They have to do this training for three months with a senior doctor, a supervisor, in a hospital which becomes a joke when you think that many hospitals are closed and that senior doctors are usually not there any more. Also, we have to consider that in the case of a specialist, like pediatricians for example, this training period takes six months. Now, all these problems have a devastating impact. And we’ve seen, just to give you another example, the number of deliveries in one clinic in a suburb of Harare, has decreased from 300 to 26 after the introduction of the foreign currency fees. Of course, those who can afford to pay 40 US dollars for the delivery services, also have to pay for the materials, as I was saying previously. And those who cannot afford these fees are delivering at home, which of course means that, in many cases, the mother and child fatalities are going to increase. This is the shocking reality of a country that used to have a model health care system and now the system has collapsed.

Now, of course in this situation many patients choose not to spend their money on health care because they need to buy food for their families. Food is extremely expensive. For many people, it’s difficult to find, and finding, for example, enough money to buy a loaf of bread can be an adventure that lasts for days. As Christophe has explained, and given the figures of WFP, there are more than 7 million people in need of food aid in Zimbabwe. In many districts of the country, the global acute malnutrition is approaching the threshold that the health system considers an emergency – above 7 percent. And we are also seeing that in many clinics where we are working and supporting, the consultations related with malnutrition problems are increasing. So we have reasons to think a malnutrition crisis is looming and could happen at any moment.

I want to say something also about HIV/AIDS because it’s still the biggest, main killer in the country by far. In 2007, for example, according to UN AIDS, the number of deaths per week was about 2,700. So that’s a very high figure that should make us think that, apart from all the problems that we have in the country, we still have a massive problem with HIV/AIDS. Now, half a million people are still in need of the treatment that will save their lives. If they don’t get this treatment, of course they will get sick in the near future and they will eventually die. But, there are already more than 200,000 people on anti-retroviral treatment , which is needed for AIDS patients at any given moment. Most of these people – more than half – have been put on this treatment in the year 2008, during the same time when the health system was collapsing. We are afraid, we fear, that all these people will not receive proper follow-up, especially if clinics keep closing, or if there is not staff appropriately trained, or adequately trained to take care of the follow-up of these patients.

MSF supports HIV/AIDS care and treatment programs in several places of the country – in a suburb of Harare, in Bulawayo, the second largest city in Zimbabwe, and in Gweru, Chilocho, and Bwera, three rural districts that we are supporting. We are covering and supporting the care of 40,000 people living with HIV/AIDS in the country. Out of which, 26,000 of them are sick enough to have been put on anti-retroviral therapy, which of course will save their lives. Among all these problems, we are having many problems to continue scaling up our programs and initiating new patients at the moment, given the circumstances of the country and because our counterpart, the Ministry of Health, also has so many problems dealing with capacity. So we are having problems to initiate these half million people who are still in urgent need of health care. But we are also having major difficulties retaining patients. For example, because of the problems of the clinics and the transportation costs, people going to the clinics from very rural areas have to pay high costs for the transportation to the clinic. Also a lot of people who don’t have money, they have to choose between feeding their families or leaving the country and going somewhere else. We have a lot of people in our programs that we have lost to follow-up because they leave their homes to try to find survival means in neighboring countries or in other parts of the country itself. And they are difficult to keep under treatment.

The problems of the people who leave their homes to find survival means in other places, who flee Zimbabwe, is also very important and I would like to introduce my colleague Rachel, as she is working in South Africa with MSF and she has a lot more information about what these people have to endure when they arrive in South Africa.

Rachel Cohen, MSF Head of Mission for South Africa

Listen:

What Christophe and Manuel have described for you is the day-to-day reality for Zimbabweans still inside the country. Unfortunately, their nightmare does not end, even when they have been able to escape Zimbabwe.

In the past several years, an estimated three million Zimbabweans – 25 percent of the entire population – have fled Zimbabwe to neighboring countries, especially South Africa. It is almost impossible to know the precise figures, but what is clear is that this is currently Africa’s most extraordinary exodus from a country not in open conflict.

Since 2007, MSF teams have been providing medical care for Zimbabweans in the border town of Musina – on farms, in townships, and in an open showground where upwards of 4,000 asylum-seekers congregate each night, exposed to harsh and unhygienic conditions. We also provide basic primary health care and facilitate access to South Africa's health system here in Johannesburg at the Central Methodist Church – a place of refuge where approximately 3,000 Zimbabweans seek shelter each night in an overcrowded de facto refugee camp.

The testimonies of our patients provide a window into a harsh reality scarcely captured. Our patients tell us of the violence they experienced or witnessed in Zimbabwe, particularly during the election period; they tell us they have not eaten for days and have survived on discarded orange peels; our HIV-positive patients tell us they are on antiretroviral treatment but have run out of drugs during their perilous journey from home.

Last night we learned of a group of 500 women and children who this weekend attempted to swim across the crocodile-infested Limpopo River to reach South Africa, only to fall prey to local bandits known as "guma-guma." Last night at the Methodist Church we heard that 5 of the women who crossed were raped, and two babies were literally taken off their mothers' backs and thrown into the river to drown.

These local gangs beat, rob, and rape; they extort what little money or possessions Zimbabweans have been able to salvage from their shattered lives in Zimbabwe with the false promise of helping them to cross the border safely.

Despite the fact that Zimbabweans literally risk their lives to flee Zimbabwe, the South African government only considers Zimbabweans as “voluntary economic migrants” and aggressively deports them – approximately 17,000 Zimbabweans are deported each month by South African authorities, according to UN and Department of Home Affairs figures. The result is that Zimbabweans live in a constant state of fear. Few seek the health care they need, and to which they are entitled under the South African constitution, out of fear of arrest and deportation.

Our medical teams treat around 4,000 Zimbabweans each month in Musina and Johannesburg. We see mainly respiratory tract infections, sexually transmitted infections, including HIV (about 25-30% of those tested in our mobile and fixed clinics are HIV-positive), gastro-intestinal and diarrhoeal conditions (including cholera), and stress-related ailments (due to the multiple traumatic events patients have endured). We are also seeing an increase in the number of cases of sexual violence and in the number of unaccompanied minors arriving in both Musina and Johannesburg. 200 people arrived at the Methodist Church just yesterday, 10 of whom are unaccompanied minors.

As if they haven’t endured enough, Zimbabweans are being forced to hide in the shadows of South African society to avoid deportation and to escape xenophobic violence within South Africa. What they need is protection. We are calling upon the government of South Africa to halt deportations and provide adequate humanitarian assistance – including some form of legal status – for Zimbabweans seeking refuge in their country.

Christophe Fournier:

Listen:

Thank you, Manuel and Rachel to have described so vividly the situation for Zimbabweans both in Zimbabwe and in South Africa. I would just like to conclude by reiterating what we are actually calling for today.

Now more than ever, an adequate humanitarian response in Zimbabwe will require unrestricted access to vulnerable populations for independent aid organizations to carry out our work. The Zimbabwean government must respect independent assessments of need, guarantee that aid agencies can work wherever needs are identified, and ease bureaucratic obstacles so that programs can be staffed properly and drugs and other urgent medical supplies can be imported quickly.

At the same time, MSF is also calling today for donor governments and UN agencies to shift to an emergency approach and respect the distinction between the provision of humanitarian aid and the pursuit of broader political objectives.

Finally, MSF is asking the government of South Africa to stop deporting Zimbabweans and to allow for the provision of appropriate humanitarian assistance, including a legal protection for Zimbabweans seeking refuge in South Africa.

And with that, we will close our remarks and take your questions. Thank you very much.