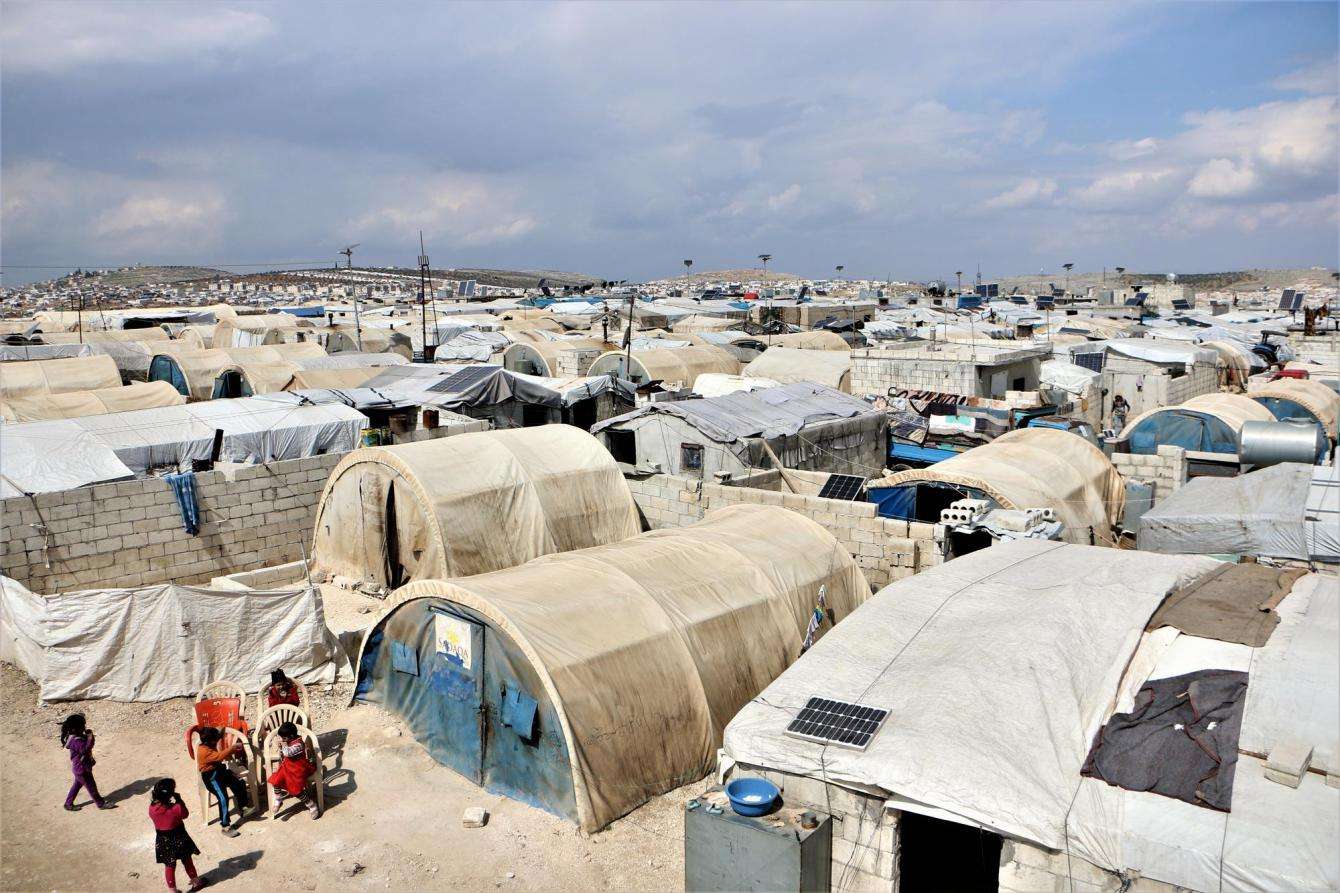

More than two million people are internally displaced in northwestern Syria, and many of them are forced to live in unhygienic conditions in overcrowded camps or makeshift shelters with limited access to basic necessities like clean water. The number of COVID-19 cases has steadily increased in the region since July. As of November 4, there were 7,059 confirmed cases—with 524 of those cases on November 3 alone, the highest number recorded in a single day. There are only three labs in the area, and they currently process fewer than 1,000 tests a day in total.

In an attempt to slow the transmission, local authorities imposed a limited lockdown on November 6, but the economic crisis and ongoing fighting make it especially challenging for people living in the camps to adapt to the new measures.

“With coronavirus, I know leaving home is risky, but I don’t have any choice,” says 25-year-old Kamal Adwan, who lives in Abu Dali camp in Idlib province. “As scary as the virus is, I can’t leave my family without food.”

Kamal and his family fled their home in rural Hama province in February 2019 after it came under heavy shelling. He now lives with his parents and 12 other family members in two adjacent tents. He is the sole income earner for his family. For Kamal, the economic repercussions of the pandemic are potentially more dangerous than the pandemic itself.

Before the outbreak, Kamal used to find work on construction sites whenever possible. Although it was never a stable job, he did his best to support his family. “When we first heard of the coronavirus, we thought it was a rumor, or nothing more than a seasonal flu,” says Kamal. “Now I know that this virus is no joke and it is directly affecting me.”

Many of the 16,000 residents of Abu Dali camp live with their extended families in crowded tents, some as small as 64 square feet. Doctors Without Borders/Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) teams run mobiles clinics and distribute hygiene kits and other relief items in Abu Dali camp and various other camps in the region.

In the camps, the risk of COVID-19 transmission is high. It is almost impossible to practice social distancing or isolate from others when needed. Regular handwashing is also a challenge, since many people rely on water collected from shared water tanks.

“My main concern is to stay as far away as possible from anyone with suspected COVID-19,” says Kamal. “The camp is overcrowded, and hiding from the virus has been challenging.”

Umm Firas, 39, is also the sole income earner for her family after her husband was half paralyzed in an airstrike on their house more than a year ago. Umm Firas earns money to support her family, including her nine children, by renovating people’s tents in the camp and mending their mattresses and sheets. Now she has to balance her family’s need for an income against the risks of going out to work.

“I stopped going out of my tent to protect myself and my family,” she says. “But sometimes I am obliged to go and look for work. I am always scared I’ll catch the virus and spread it to my children, but what else can I do?”

Three of Umm Firas’s daughters used to go to school. Schools across northwestern Syria took measures to reduce the risks of transmission, including the requirement for students to wear face masks. These can be bought from local pharmacies for one Turkish lira—a price that many parents here cannot afford. So then they are forced to stop sending their children to school. Some teachers have tried to find alternative solutions, such as allowing students to use old pieces of cloth to cover their faces.

“The teacher used to ask my daughters to put masks on, but what do you expect them to say?” says Umm Firas. “I have never bought a mask—I can barely buy bread. When I have the choice, I always go for bread.”

Forty-year-old Umm Ahmed is also finding it difficult to cope. Originally from Qalaat Al-Madiq, in Hama province, Umm Ahmed fled her home with her husband and seven children in 2012 and found refuge in Qah, in Idlib province. In 2014, they moved from Qah to Deir Hassan, where they have lived since. The family lives in a one-room tent.

Umm Ahmed’s husband is bedridden and cannot work. She works as a hygiene assistant in one of the hospitals in Ad-Dana district, in northwestern Syria, but was forced to stop when she experienced kidney failure a few months ago.

The camp where Umm Ahmed lives hosts around 50 families who all share a single water tank and three toilet blocks. “It’s impossible to wash your hands regularly in the camp without putting yourself at risk,” she says.

As the economic situation for Umm Ahmed’s family worsens, she is finding it increasingly difficult to afford soap and detergents to protect herself and her family from COVID-19. MSF teams recently provided Umm Ahmed and other families with a hygiene kits containing soap, detergents, and buckets.

“There are still things we can do to avoid catching the virus,” says Umm Ahmed. “I’ve stopped going out as much as I can, and I avoid being around other people. It keeps me and my family safe. But I can’t ban my children from playing outside with the other kids. They’re young, they need to play—and our tent is very small. I understand it’s a risk, but how can I stop them?”

Even prior to the lockdown, daily life had become much more expensive, and many people were struggling to survive. “Earlier in October, markets, mosques, and schools were closed for some days, but they were open again soon after,” says Hassan, MSF logistics manager. “Lots of people rely on markets to make a living, so they can’t afford to be out of business for a long period of time.”

After years of conflict, the health care system in northwestern Syria was already fragile—the COVID-19 outbreak has made the situation worse. There are just nine dedicated COVID-19 hospitals for a population of approximately four million. There are also 36 isolation and treatment centers providing basic care for patients with mild symptoms.

“Idlib province has become like a huge prison: people can’t move south or north, and they’re stuck here in the middle,” says Hassan. “They think that the virus will reach them and their families at some point. They only hope it won’t get to them all at once. The health care system simply couldn’t manage to treat a lot of COVID-19 patients at once.”

MSF has teams of Syrian staff working in pockets of Idlib province providing care and relief items to displaced people through mobile clinics. MSF also runs a burn care unit in Atmeh and provides remote support to several health facilities, including through the co-management of three hospitals in Idlib province.